Understanding Pediatric Stroke with Dr. Adam Kirton

Dr. Kirton is an attending Pediatric Neurologist at the Alberta Children’s Hospital and Associate Professor of Pediatrics and Clinical Neurosciences at the University of Calgary. His research focuses on perinatal stroke with two major aims. One is to understand why such strokes occur and develop means to prevent them. The other uses advanced technologies including neuroimaging and non-invasive brain stimulation to measure the response of the developing brain to early injury and generate new therapies. Karolina recently chatted with Dr. Kirton regarding his research and his clinical work.

Karolina Urban (KR): What is the current understanding of perinatal stroke?

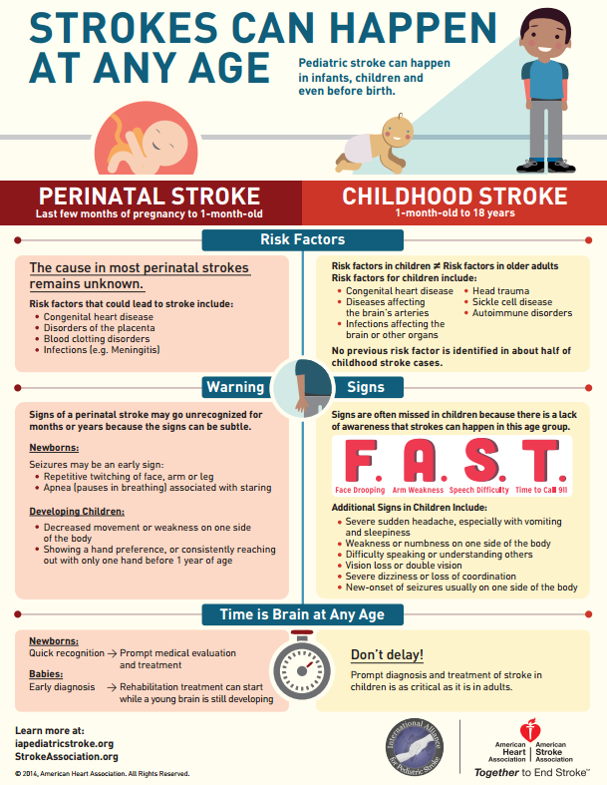

Dr. Adam Kirton (AK): Poor, but rapidly improving. Perinatal stroke means a focal vascular brain injury acquired before or near birth. There are different types if you consider what vessels are affected (arteries or veins), whether they are blocked or break (ischemia versus hemorrhage), and injury timing (fetal versus neonatal). We understand little of what causes any of them. The most common is neonatal arterial ischemic stroke where a cerebral artery is blocked near birth leading to focal brain injury, usually presenting acutely as neonatal seizures. We suspect emboli from the placenta, possibly secondary to acute infectious or inflammatory disease, account for most cases. This is supported by multifocal lesions in many babies, abnormal inflammatory markers in subjects, and virtually zero recurrence risk later in life. However, obtaining placental pathology is not possible in most cases, often preventing the definitive link in most cases. The other forms of perinatal stroke are different but suffer from similar limitations regarding pathophysiology. It is important to note that there is nothing a mother can do to prevent perinatal stroke from happening.

KU: You mention the use of neuroimaging techniques to understand perinatal stroke? Can you tell me about some of the methods you use and how they can be used to understand the pediatric brain?

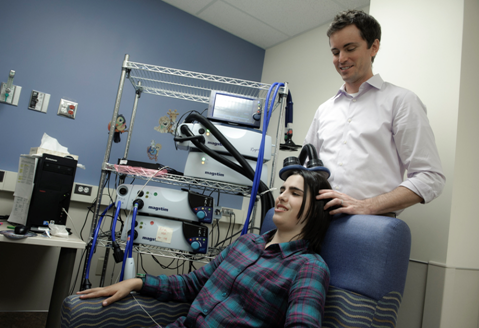

AK: Diagnostic imaging has vastly improved perinatal stroke detection and classification. Examples include diffusion MRI which is highly sensitive to acute infarction and imaging of the vessels themselves such as MR angiography (MRA) and venography (MRV). Advanced neuroimaging is expanding our understanding of how young brains develop following such injuries. Examples include task and resting state functional MRI, MR spectroscopy, diffusion tensor imaging (DTI) and others. Imaging also helps us use other tools to map the brain such as Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation (TMS). Taken together, these tools are building individualized pictures of brain organization that in turn have facilitated new therapies such as non-invasive neuromodulation.

KU: Currently, many signs of perinatal stroke may go unrecognized for months or years. Can you describe what some of the difficulties with recognition are?

AK: Even with a large brain injury, the newborn often looks well and unless they have seizures, neonatal strokes often go undetected. Clinical presentation typically occurs at 4-6 months of age when parents note that one side of the body is not moving as well as the other. Such early hand preference is always abnormal before the first birthday and usually indicates early hemiparetic cerebral palsy which is usually caused by perinatal stroke. Efforts are underway to better educate primary health care providers to recognize these signs to facilitate earlier intervention.

KU: Can you speak to some of the risk factors or symptoms that are often that may be a warning sign of a childhood stroke?

AK: Stroke in children is different than both newborns and adults. Children present much like adults with the sudden onset of focal neurological deficits. Most common causes are diseases of the cerebral arteries themselves that may include infection or inflammation, injury (dissection) or genetic diseases like moyamoya. Cardioembolic stroke is also relatively common. Typical adult stroke risk factors (high blood pressure, diabetes, dyslipidemia, atrial fibrillation) are rare in children. Most perinatal stroke results from placental embolism.

KU: Your current clinical trial called “the plastic champs trial” is funded by the Heart and Stroke Foundation of Alberta. Can you explain what constraint-induced movement therapy (CIMT) is and how it may modulate brain plasticity?

AK: In patients with hemiparesis, CIMT restrains their strong side with a cast or splint during therapy to help “force” the brain to use the weak side better. Evidence supports long-term efficacy in adults with stroke and probably in children with hemiparetic cerebral palsy. Our early trials suggest combining such therapy with targeted non-invasive brain stimulation mat further enhance the ability of the brain to learn.

For more information on this trial, click here.

KU: A major part of your research is using Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation (TMS), a non-invasive method that studies the electrical activity of the brain (specifically the neurons), can you tell me about what you hope to understand with this method? How can it help us better understand brain injury?

AK: TMS can both measures and modulate the brain. Giving single or pairs of magnetic pulses to the motor cortex and measuring the muscle responses that results can explore detailed brain excitability and connectivity. Given repetitively (called rTMS), TMS can modulate brain functions with lasting effects, leading to therapeutic potential. High levels of evidence have established efficacy for rTMS in adult major depression and it is currently being tested in many other neurological and psychiatric conditions.

KR: Now to the hard questions, what led you to become interested in this research field and to become pediatric neurologist?

AK: Hard to say. In medical school I did not like neuroscience (too complicated) or children (they intimidated me). Through experience, I learned that sometimes things that seem the most challenging also come with the greatest rewards. I became fascinated with clinical neuroscience where the developing brain is in many ways the most interesting. Combining this with the enjoyment of helping young children and families, often during the most difficult circumstances, lead me to where I am now.

KR: From your clinical experience, what do you think are some of the most important keys for parents to keep in mind when it comes to their children’s health?

AK: Kids can usually fix themselves. Brain development is a natural process that occurs with normal stimulation and experience best achieved with a balanced lifestyle.

KR: Who is Dr. Kirton outside of research?

AK: Who knows?

About Dr. Kirton:

Dr. Kirton is an Attending Pediatric Neurologist at the Alberta Children’s Hospital and Associate Professor of Pediatrics and Clinical Neurosciences at the University of Calgary. He has published over 120 peer-reviewed papers, 20 book chapters, supervised over 40 research trainees, and earned over $20M in external research grants including CIHR Foundations funding in 2015. He directs the Calgary Pediatric Stroke Program, Alberta Perinatal Stroke Project, ACH Pediatric Non-Invasive Brain Stimulation Laboratory and University of Calgary Noninvasive Neurostimulation Network (N3). You can visit his website here.

The opinions expressed in this blog post are the author’s own.