'Kinecting' with Clinicians

Exploring the benefits and challenges of integrating Virtual Reality and Active Video Games within pediatric rehabilitation.

About my research:

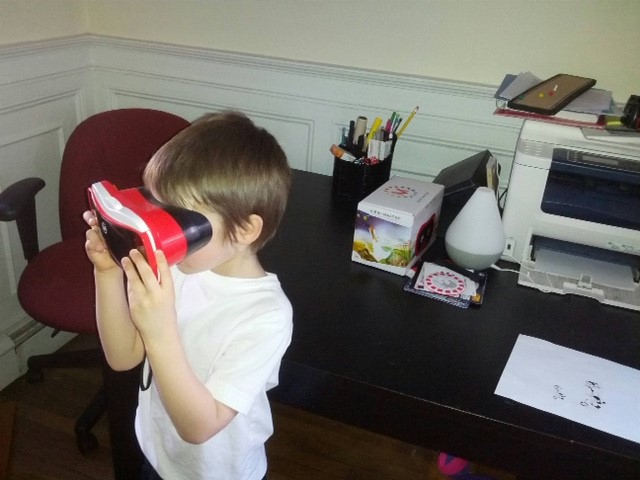

As a physiotherapist with clinical experience in pediatrics, I am interested in exploring how virtual reality (VR) systems and active video games (AVGs) can be integrated within pediatric rehabilitation. The prevalence of VR and AVGs in clinical practice is a fairly new phenomenon. Although Sony introduced full body game interaction with their EyeToy console, Nintendo took the gaming world by storm in 2007 with the Wii and Wii Fit platforms. This system moved mainstream video gaming beyond handheld controllers and into the realm of full body movement. The popularity of these consoles unleashed a torrent of clinical and research interest in the potential to use these active video games in rehabilitation contexts. ‘Wii-habiliation’ was a hot topic!

Therapists and researchers were excited about the many possible benefits of integrating these VR and AVGs into therapy. These advantages include the potential to motivate clients to undertake more frequent practice repetitions, the ability to elicit functional movement through distracting games, the potential for children to learn through the abundant visual and auditory feedback provided about movement performance and results, and the option to use these games as part of home exercise programs. In tandem, people recognized some of the potential disadvantages, including the chance of repetitive stress injuries, the fact that users could interact with the games via undesired movement patterns, and the reality that some of the negative feedback provided by the Wii may be discouraging to certain patient populations.

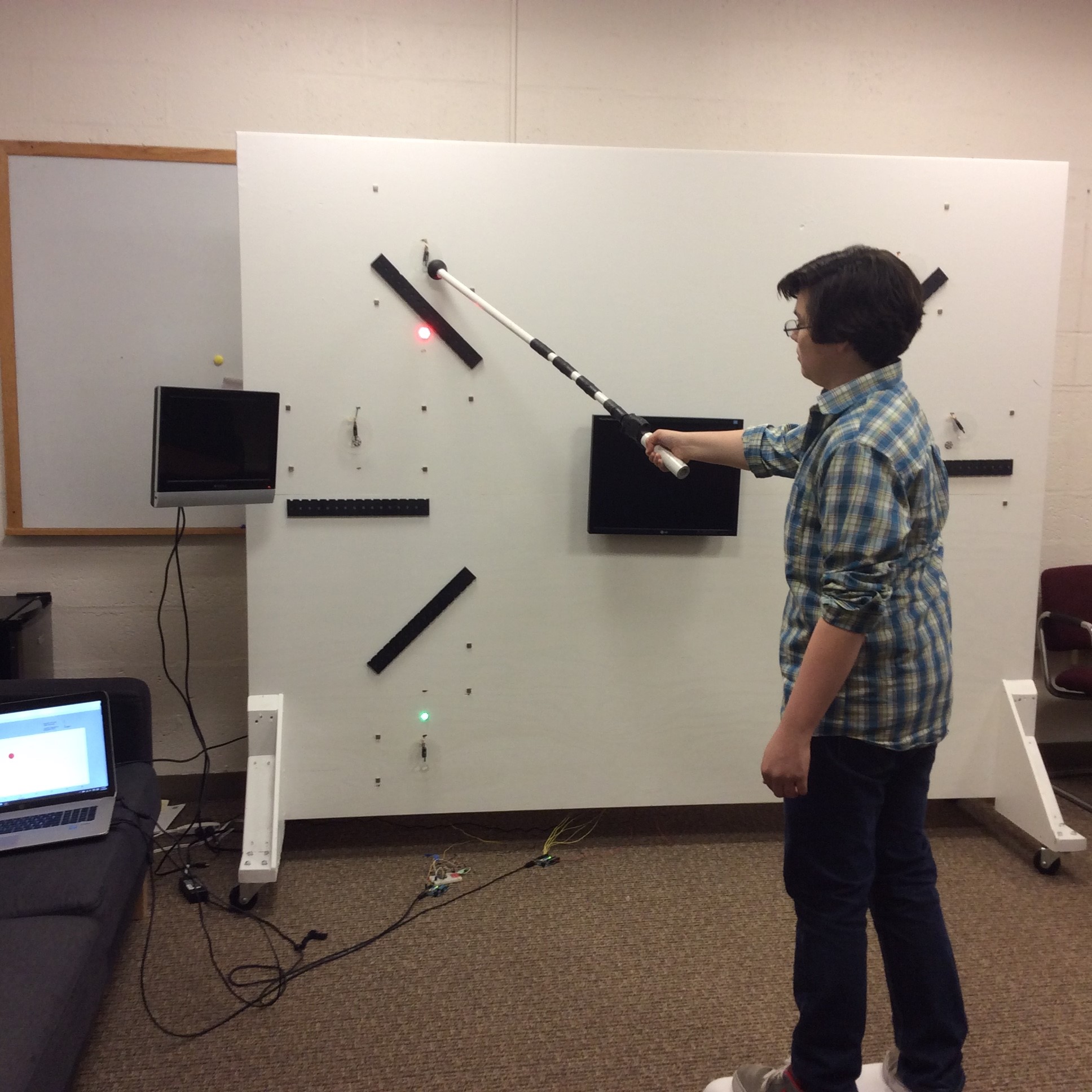

More recent markerless motion-capture systems, such as the Microsoft Kinect, have enabled game interaction via unencumbered body movement. This feature overcomes some of the limitations of the Wii, including the potential for ‘cheating’ through the use of small Wiimote movements, and the restricted play space associated with standing on a force plate. Rehabilitation-specific systems that use the Kinect sensor, such as Jintronix and MiTii, are making tele-rehabilitation accessible and cost-effective. These systems overcome some of the limitations of off-the-shelf games by allowing precise parameter selection and tracking of therapeutically relevant variables. Developers can use Microsoft’s Kinect SDK to create their own games and applications. Other systems, like Timocco, simply use a webcam and an internet connection. These are just a few of the many examples of accessible VR systems that can be used in clinics and homes (see here for a growing list of other companies).

Much of the excitement about VR and AVG use in rehabilitation relates to 2 things: 1) The potential for gaming to increase motivation and engagement, which is thought to encourage adherence to the substantial practice dosage and repetitions required to elicit functional change; and 2): the potential for VR and AVGs to promote motor learning, since these systems – to varying degrees – take advantage of attributes of motor learning principles, such as feedback, repetitive practice, ability to individualize challenge levels and enriched environments, which further solidify their theoretical appeal.

As a physiotherapist and researcher, I’ve been interested not just in knowing whether these VR and AVG systems are effective to promote better functioning in children and adolescents with neuromotor impairments, but also in how they compare to traditional interventions, and how to support clinicians interested in their use. These questions include:

- How can practice in a 2D or 3D virtual environment promote motor learning of new skills to a similar or greater extent than practice in a conventional physical environment?

- What is the role of motivation and engagement in virtual environments for motor learning? What specifically about virtual environments do children find motivating and/or engaging?

- Do skills learned in a virtual environment transfer to real life?

- How can we help therapists make decisions about which games to use for different types of clients?

- How should therapists monitor, progress and document their VR-based therapy interventions?

- What knowledge translation opportunities exist for therapists to learn more about how to integrate VR systems into their clinical practice?

My research program seeks to contribute answers to these questions, in laboratory and clinical settings, using immersive VR systems in the lab, rehabilitation-specific tele-rehabilitation systems, and off-the-shelf commercially available active video games. Some past and current projects include:

- Developing knowledge translation resources based on learning needs: Physical and occupational therapists need support in the form of knowledge translation learning resources to develop their skills in using VR. In collaboration with Stephanie Glegg at Sunny Hill Health Center for Children in Vancouver, BC, we are building on my postdoctoral research project funded by the Ontario Stroke Network to develop and to evaluate online KT resources to meet this need. We have just completed an online survey of Canadian clinicians’ VR experience and learning needs related to integrating VR into practice and will shortly begin recruitment in the US and internationally. Survey findings will inform KT resource content to be housed on www.vr4rehab.com. This site will soon be home to a range of online resources (including www.kinectingwithclinicians.com, a Kinect-specific resource under development with Dr. Judy Deutsch (Rutgers University), Dr. Emily Fox (University of Florida), Dr. Sujata Pradhan (University of Washington), and Dr. Debbie Espy (Cleveland State University) to assist clinicians in keeping current with emerging research evidence on VR for rehabilitation, in developing new knowledge and skills in applying VR to practice, and in accessing networking and learning opportunities in the field. Ultimately, accessible evidence-based resources will support effective integration of VR and video gaming systems in a variety of practice settings.

- Evaluating whether a 1-week VR-based therapy ‘jump-start’ can enhance the effects of a home Kinect AVG-based exercise program in children and youth with cerebral palsy (funded by the Ontario Federation for Cerebral Palsy and the Ottawa Children’s Treatment Center)

- Developing and evaluating the psychometric properties of a rating form to document the movements elicited during VR and AVG game play

- Developing and evaluating a KT intervention for therapists to promote motor learning-based use of VR in stroke rehabilitation (funded by the Ontario Stroke Network)

- Exploring the motor learning potential of practice in VR, including evaluating the role of different kinds of feedback in virtual environments and comparing the learning of a new task in a virtual and a physical environment

- Enhancing the Motor Learning Strategies Rating Instrument: Jennifer Ryan is undertaking MSc research to further develop the psychometric properties of the MLSRI-20, an observer rating instrument I developed with colleagues at McMaster University as part of my PhD

About me:

I graduated from the University of Ottawa’s physiotherapy program in 2001 and worked clinically as a physiotherapist in pediatric acute care, rehabilitation and school health support. This clinical experience led me to an MSc in the School of Rehabilitation Science at McMaster University in Hamilton, where I explored variability in recovery patterns after pediatric acquired brain injury. I knew I wanted to continue my research journey, and immediately began a PhD, under the exceptional guidance of Dr. Cheryl Missiuna and my committee of Dr. Virginia Wright, Dr. Laurie Wishart and Carol DeMatteo. This PhD work was based in my clinical interest in the use of virtual reality and active video games in rehabilitation. My PhD focused on use of the Nintendo Wii in pediatric ABI rehabilitation, and in particular, on how clinicians could use motor learning strategies during VR-based interventions, and how this compared to use of motor learning strategies during ‘usual’ care. I was very fortunate to be supported during my doctoral studies at McMaster by the Canadian Child Health Clinician Scientist Program, the CanChild Center for Childhod Disability and the McMaster Child Health Research Institute. Following my PhD, I undertook a postdoctoral fellowship in the Motor Control Laboratory at the University of Ottawa under the supervision of Dr. Heidi Sveistrup and Dr. Mindy Levin, where I continued exploring VR and active video games from a motor learning perspective. I’m now happily building my research program in Boston, MA, where my family and I are enjoying exploring everything that the area has to offer. And yes, my kids and I are gamers!

About my lab:

The Rehabilitation Games and Virtual Reality (ReGame-VR) lab focuses on promoting the sustainable, evidence-based integration of VR and active video gaming (AVG) systems into rehabilitation. We explore how VR-based therapy can improve motor learning, balance, functional mobility and participation in children with neuromotor impairments. We use motor learning paradigms to understand how virtual environments can exploit key motor learning principles known to be critical for rehabilitation (such as motivation, task-oriented training and multisensory feedback) and create transfer-oriented practice conditions. We also partner with hospitals, clinics and schools to evaluate the effectiveness of VR and AVG treatment programs (such as Jintronix and Timocco) to promote functional recovery from neurological impairments. Finally, we produce and evaluate the effectiveness of accessible knowledge translation resources for clinicians interested in integrating VR/AVGs within clinical practice. Our mission is to produce clinically-relevant, high-quality evidence in the field of virtual rehabilitation.

Contact information:

Dr. Danielle Levac, BSc. PT, MSc., PhD

- Rehabilitation Games and Virtual Reality (ReGame-VR) Lab

- Twitter: @DanielleLevac and @regamevr

- Link to published work

- Link to Google Scholar

The opinions expressed in this blog post are the author’s own.